What Does It Mean Today to Be Evidence-Based in Teaching? Part 2

Turning Student Struggles Into Better Teaching Materials

The Problem: Students Weren’t Reading the Textbook

We’ll start with a confession: our textbook is really good. As Utah teacher Sarah Gale put it during her presentation at the Teaching Innovation Potluck:

“The textbook is excellent. The graphic examples are clear and illustrative, and the interactive code boxes really allow the students to experiment with the code and not submit until they’re confident in their answer.”

But even with a great textbook, many teachers told us the same thing: Students weren’t always reading! Or if they were, they weren’t understanding enough to transfer that knowledge into our Investigation Notebooks, where the real-world application and critical thinking happens.

So what do we do when students aren’t learning from materials we know are strong? We don’t just invent something new in isolation, and we don’t blame the students.

We do what we always do at CourseKata: we kata! We run a data-driven continuous improvement routine.

The Kata Routine

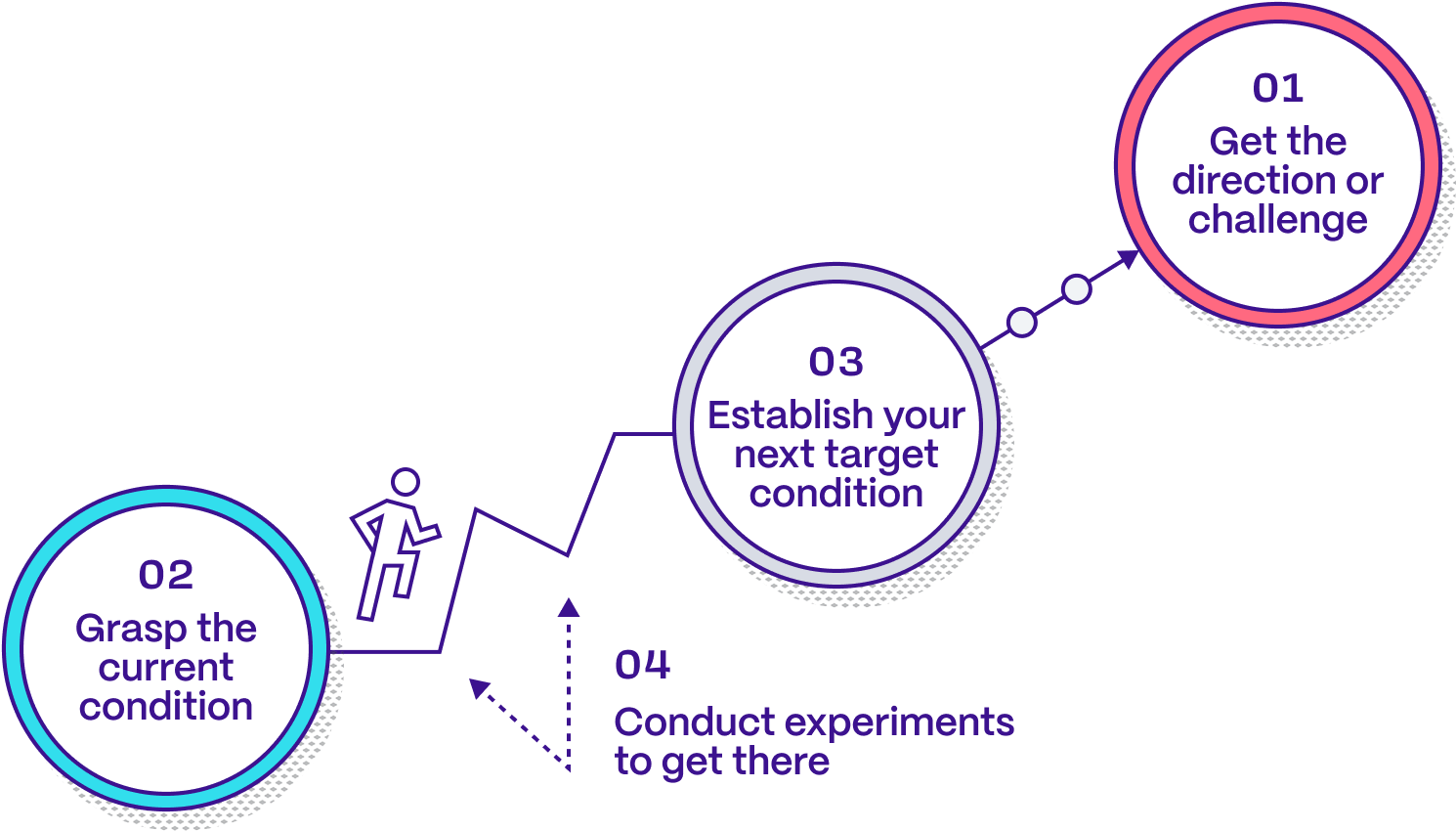

Kata is our “secret sauce” for continuous improvement. It’s a simple but powerful routine for using data and experimentation to improve teaching and learning:

Adapted from Mike Rother's Toyota Kata website at the University of Michigan.

To tackle this reading/engagement problem, we ran a Kata cycle with our Teaching Improvement Groups (TIGs), monthly meetings where teachers, curriculum developers, and researchers come together to improve CourseKata.

Step 1: Direction / Challenge

Our challenge was clear: All students should be able to engage in authentic data investigations right in a high school classroom.

Step 2: Grasp the Current Condition

Teachers told us that to make this happen, they were supplementing heavily, creating their own bridge activities between the textbook and the investigations. It took time, it took effort, and everyone was doing it on their own.

So our TIGs inventoried what was missing. We found that students needed a more active, guided way to learn specific concepts and skills before launching into full investigations.

Step 3: Set the Target Condition

We envisioned teaching materials that would:

- Engage all students, not just the ones eager to say “the right answer.”

- Support students who hadn’t done all the reading without discouraging those who had.

- Introduce statistical and data science ideas coherently and interactively.

- Align with our Practicing Connections Hypothesis, that understanding comes from making connections between concepts.

Step 4: Experiment Toward the Goal

TIGs developed two prototype "Overview Notebooks": one for Chapter 3 and one for Chapter 7. They tested them in classrooms at different points in the year, then reconvened to share data, challenges, and design tweaks.

Through this iterative process, we co-created this bridge between reading and investigation, designed to activate prior knowledge, build connections, and prepare students for deeper analysis.

One teacher after piloting an overview notebook in his class said: “How can I get more of these RIGHT AWAY?!”

Beyond Overview Notebooks

Once we had a working model, our TIGs identified other teaching materials that filled various needs:

- Paper worksheets for drawing and annotating

- Mini-notebooks for targeted practice

- Mini-quizzes for fast checks of specific concepts

By the start of Fall 2025, we had teaching materials for Chapters 1-7 ready to go.

The response so far? Overwhelmingly positive. Instructors are telling us that their problem now is that there are so many great materials and they don't have time to use them all.

The Work Continues

We’re not done. Our newest TIG cohort is now investigating how teachers navigate these materials: How do they decide what to use? When? For whom?

This is what being evidence-based looks like for us. Not a static claim about what works, but a continuous, sustainable practice of using evidence to make teaching better. The Overview Notebooks weren’t dreamed up by a singular genius. They were built through teachers, researchers, and data working together in the Kata routine.